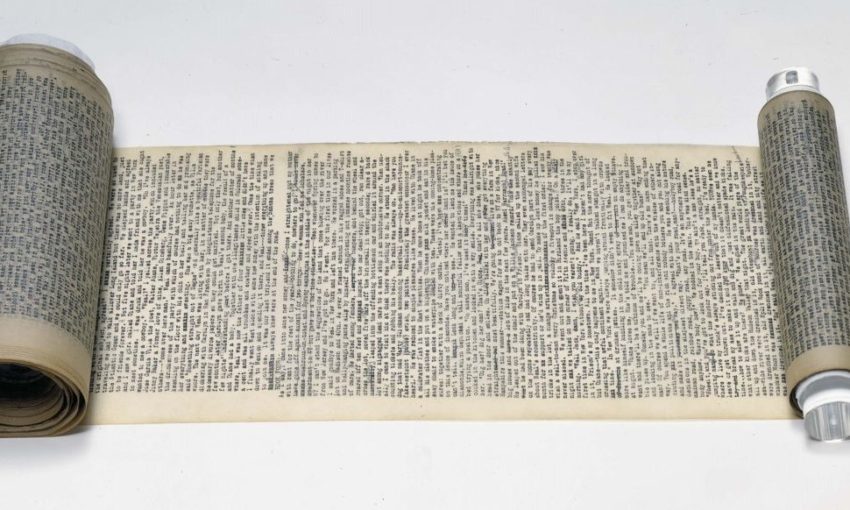

The act of changing paper was eliminated from the process. It would allow him to write his book as one giant page. Kerouac reportedly could type around 100 words per minute, which is very fast, so the idea of a continuous sheet of paper would have been appealing to him in 1951. Today, we have computers and word processing software, but if you have ever composed anything on a typewriter, you know that the time it takes to pull the finished page out of the carriage and feed in a new page slows you down and breaks your rhythm. It was in their apartment, over a three-week period, that Kerouac wrote the scroll version of his most important book. He was married at the time to Joan Haverty, and the two of them were living in Manhattan, on West 20th Street. Jack Kerouac taped these 12 sheets of tracing paper together and fed them into his typewriter in the spring of 1951. I thought about the writing process, and I thought about Jack Kerouac the writer. I didn’t think about the events or characters in On the Road. I stood there for a long time and I looked at this object, this extraordinary artifact from a writer who died forty years ago. There are handwritten changes and additions in the margins and on the page. On closer inspection, you can see that the scroll has been edited. It starts at the top and goes for 120 feet. There are no indentations for paragraphs, no page breaks. The next thing that I noticed about the Scroll is that it is one continuous stream of typewritten words. It was mounted on a continuous white sheet of backing paper to help support and preserve the manuscript.

The Scroll paper is thus thinner and more fragile than what I had envisioned.

He taped ten of these sheets together, to form a continuous page 120 feet long, wide enough to fit into a typewriter carriage. Instead, what Kerouac really used was 12 foot long sheets of architectural tracing paper.

I had read somewhere that Kerouac used teletype paper for the Scroll, so I expected to see the telltale sprocket holes on the sides. I walked up to the second floor of the College’s main building, to the Center for Book and Paper Arts, and there, laying in a long glass display case was Kerouac’s Scroll, what seemed like almost 100 feet of it rolled out flat, the rest curled up on a glass rod. It was being shown at Columbia College as one of the stops in a four year tour of museums, universities and libraries. I took a trip to the South Loop in Chicago to visit the Holy Grail of American Literature - the Kerouac Scroll manuscript of On the Road.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)